NVIDIA flagship data center GPUs in the NVIDIA Ampere, NVIDIA Hopper, and NVIDIA Blackwell families all feature non-uniform memory access (NUMA) behaviors, but expose a single memory space. Most programs therefore do not have an issue with memory non-uniformity. However, as bandwidth increases in newer generation GPUs, there are significant performance and power gains to be had when taking into consideration compute and data locality.

This post first analyzes the memory hierarchy of the NVIDIA GPUs, discussing the power and performance impacts of data transfer over die-to-die link. It then reviews how to use NVIDIA Multi-Instance GPU (MIG) mode to achieve data localization. Finally, it presents results for running MIG mode versus unlocalized for the Wilson-Dslash stencil operator use case.

Memory hierarchy in NVIDIA GPUs

Consider the abstract view of the memory hierarchy with two NUMA nodes depicted in Figure 1. When a streaming multiprocessor (SM) on node 0 needs to access a memory location in the dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) of node 1, it must transfer data over the L2 fabric. In the case of NVIDIA Blackwell GPUs, each NUMA node is a distinct physical die, which adds latency and increases the power required for data transfer. Despite the added complexity, NUMA-unaware code can still achieve peak DRAM bandwidth.

To address these drawbacks, it is beneficial to minimize data transfers between NUMA nodes. When a single memory space is presented to the user, NVIDIA architecture employs coherent caching in L2 to reduce data transfers between NUMA nodes. This mechanism helps prevent repeated accesses to the same memory address from refetching data over the L2 fabric interface. Ideally, once the address is fetched into the local L2 cache, all subsequent accesses to the same address will hit the cache.

Before the introduction of coherent caching, the unified L2 cache allowed all SMs to achieve peak bandwidth (as in NVIDIA Volta), though latency varied depending on the proximity of the SM to different L2 segments. With the NVIDIA Ampere generation, larger chips introduced a hierarchy of NUMA nodes, each with its own L2 cache and a coherent connection to others.

While large data center GPUs since NVIDIA Ampere architecture have used this design (unlike smaller gaming GPUs), the L2 fabric connection sustains peak bandwidth as mentioned in NVIDIA Blackwell Ultra architecture.

Two challenges have emerged as GPUs continue to grow: increased latency and power limitations.

- Increased latency: Accessing distant parts of the L2 cache has led to growing latency, which impacts performance, particularly for synchronization.

- Power limitations: On the largest GPUs, power consumption becomes a limiting factor when tensor cores are active. Reducing power consumption through localized L2 access enables decreasing the L2 fabric clock and raising the compute clock through a Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) mechanism associated with GPU Boost. In this way, tensor core performance can be significantly improved.

MIG reduces data transfers between NUMA nodes. Introduced with the NVIDIA Ampere architecture, this feature enables partitioning a single GPU into multiple instances. By using MIG, developers can create one GPU instance per NUMA node, thereby eliminating accesses over the L2 fabric interface.

This approach does come with its own set of costs, including the overhead of communicating between different GPU instances using PCIe. The following section presents results from running workloads using MIG mode and unlocalized memory to demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach.

Data localization using MIG

MIG enables supported NVIDIA GPUs to be partitioned into multiple isolated instances, each with dedicated high-bandwidth memory, cache, and compute cores. This enables efficient and high-performance GPU utilization across multiple users or workloads. MIG can achieve up to 7x more GPU resources on a single GPU. It allows multiple virtual GPUs (vGPUs) and, consequently, virtual machines (VMs) to run in parallel on a single GPU, while providing the isolation guarantees that vGPUs offer.

The capabilities provided by MIG can be leveraged to achieve NUMA node localization. By creating one MIG instance per NUMA node, you can ensure isolation between different GPU instances. This approach helps eliminate traffic between NUMA nodes.

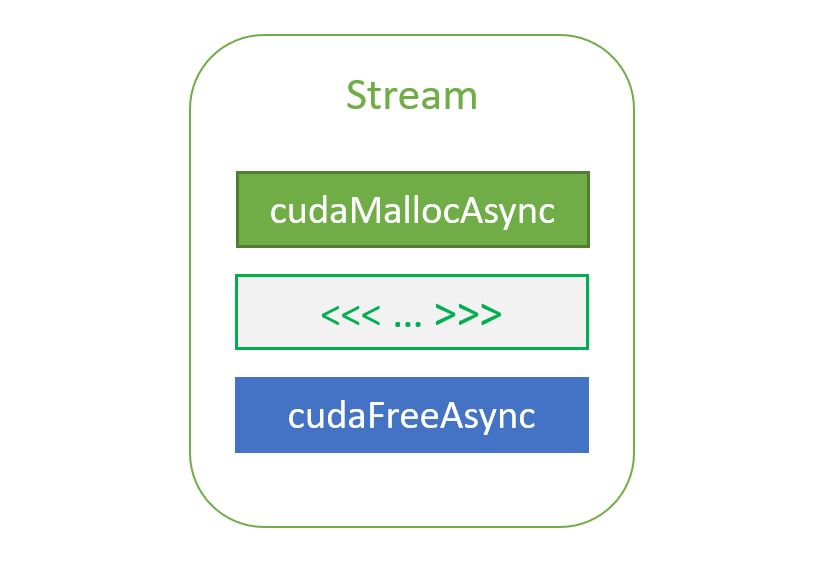

MIG allows the splitting of the actual GPU into GPU instances (GI), in which one or more compute instances (CIs) are defined. A CI contains all (in the case of a single CI per GI) or a portion of the SMs belonging to a GI. To enable localization within a GI, the idea is to create two GPU instances mapped onto each NUMA node. On a Blackwell GPU, you can enable MIG mode and list the available GPU instance profiles, as shown with the code in Figure 2.

Because Blackwell has two NUMA nodes (one per chiplet), look for the profile with the most SMs of which there are two instances. As shown in Figure 2, this is the profile with ID 9, of which there can be two instances. Each instance will have 89 GB and 70 SMs. Using two such instances will result in only 70×2=140 SMs in total, rather than the full 148 SMs on the device.

At this point, it’s necessary to create a CI in each GPU instance. This can be done using the commands shown in Figure 3. The main GPU and the GPU instances now have their own identifier hash codes. Use those for the two NUMA nodes:

MIG 3g.90gb Device 0: (UUID:

MIG-ee2ec0e5-0dda-5591-9ee7-4ae51028b6fa)

MIG 3g.90gb Device 1: (UUID:

MIG-2bbb368b-7cb0-53da-b1a4-7ace0652a197)

To use these devices, add them to the CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES environment variable. For example, to run a two-process MPI job, you could create a wrapper script (wrapper.sh):

#!/bin/bash

#

case $SLURM_PROCID in

0)

CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES=”MIG-ee2ec0e5-0dda-5591-9ee7-4ae51028b6fa”

;;

1)

CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES=”MIG-2bbb368b-7cb0-53da-b1a4-7ace0652a197”

;;

esac

$*

Then launch the MPI jobs:

$ mpirun -n 2 ./wrapper.sh my_executable

Finally, when all the work is done, the MIG mode can be turned off.

What are the benefits of localization with MIG?

As an example application to demonstrate the benefits of localization with MIG, examine the Wilson-Dslash stencil operator, a key kernel for lattice quantum chromodynamics (LQCD) drawn from the QUDA library. This library is used to accelerate several large LQCD codes, such as Chroma and MILC.

The Dslash kernel is a finite difference operation on a 4D toroidal lattice, where data at each lattice site is updated depending on the values of its eight orthogonal neighbors. The four dimensions in this case are the usual spatial dimensions (X, Y, Z) and the time dimension (T). The kernel is memory bandwidth-bound.

If the lattice is decomposed onto two NUMA nodes equally, say along the time axis, then each domain will need to access sites on the T-dimension boundaries of the other domain. As shown in Figure 5, green lattice sites on the boundaries of the subdomains need the red sites to complete their stencils. The lattice is notionally laid out onto the two NUMA Nodes. Green sites need red-sites to complete their stencils. Possible data paths are regular memory access (black arrows) when unlocalized, or MPI message passing through the host in MIG localized mode (black arrows).

The most convenient way to access neighbors would be through the Shared L2 cache and the interconnect. However, when operating in MIG mode this path requires communication between the MIG instances through MPI using PCle or NVLink. As a result, this path will be slower compared to accessing the main memory attached to the MIG instance.

Workloads that require little to no communication between two MIG instances will tend to benefit more using the MIG mode. Instead, one packs the black sites on the boundaries and sends them through MPI. This step introduces additional latency (buffer packing, sending, and unpacking). While it saves GPU power by not using the shared L2 cache-to-cache interconnect, it does use power for its transfer through the host (for PCIe, for example).

The amount of data that needs to be transferred between the two processes is related to the number of face sites to be transmitted in the messages, specifically to the surface three-volume orthogonal to the direction of the split. For this example, the split is always in the T-direction, so that each NUMA node notionally ends up with (Ns Nt)/2 sites, where Ns is the number of sites in our spatial volume and Nt is the length of the time dimension. The surface to volume ratio is Ns/(Ns Nt/2) = 2/Nt. In the case of the problems, Nt=64 is considered and the surface-to-volume ratio stays constant at 1/32 ~ 3.13%.

Figure 6 shows the unlocalized case. The global memory is made up of two memories connected to the NUMA nodes through memory controllers. The colored highlights on the lattices indicate that data may come from either the local DRAM or from the remote DRAM through the shared L2.

This is to be compared with the baseline case, where MIG is not employed. Neither the data nor the processing are localized in this case, and the scenario is better represented with Figure 8. Each NUMA node receives its data both from its local memory controller and also from the other NUMA node. In fact, there is only one global lattice and the separation onto two parts for the two NUMA nodes in the figure is artificial.

In this scenario, thread blocks to process a collection of sites are assigned to the various NUMA nodes purely at the whim of the scheduler. Since the data is distributed evenly over the two NUMA memories, much more data is transferred across the shared L2 than in the case of the MIG localization where only the minimally required surface sites were transferred. This can incur a significant power cost.

On the other hand, the entire operation may be carried out with a single kernel. Latencies incurred can be avoided by packing buffers for message passing, and accumulating the received faces at the end.

For the experimental results, look at the speedup in workload execution with various GPU power limits in watts. The speedups are the ratios of the wallclock times taken by the unlocalized and MIG approaches running at identical power limits (for example, both at 700 W).

As shown in Figure 7, at a GPU power limit of 400 W, MIG outperforms the unlocalized data with speedups of up to 2.25x depending on the volume of the workload. The reason behind this is the power consumed by the L2 fabric interface becomes a limiting factor when the GPU is running at a low power limit. With MIG mode, since there is no L2 fabric power being consumed to transfer the data between NUMA nodes, workloads can run much faster.

However, when the GPU power limit is increased, MIG mode performs slightly worse in the case of the experiments represented by the grey, dark green, and black lines in Figure 9, and part of the green. This is because at higher power limits, the extra latency included by the message passing can outweigh the benefits of the localization.

As it turns out, the smaller cases (especially those indicated by black and dark green lines in Figure 7) never exhaust available power at higher power limits even in the unlocalized case. As such, they benefit little from the GPU power saving won by localization, and at these smaller volumes the latencies due to kernel launch are much more noticeable. The larger volumes (the green, for example) require more power and hence can gain an advantage over the unlocalized setup even at higher power limits.

Get started with MIG-based NUMA node localization

Local L2 caching in NVIDIA data center GPUs can impact performance in NUMA-unaware workloads. Our experiments using the Wilson-Dslash operator in MIG mode show that when the GPU is running at lower power limits and data transfer over MPI (PCIe/NVLink) is low relative to local memory accesses, MIG-based NUMA node localization can yield speedups of up to 2.25x compared to the unlocalized case at the same power limit.

While systems running at a higher 1,000 W power envelope may achieve greater absolute performance than a 400 W configuration, MIG-based localization provides clear advantages under power-constrained conditions. In lower-power scenarios, it enables significantly faster performance, making it an especially effective optimization when operating within strict power limits.

However, in general, MIG does not offer the flexibility required to consistently achieve effective data localization, especially as interprocess communication overhead becomes more pronounced at higher power limits. MIG is only supported for use cases that are too small to fit on a GPU. For this reason, it is not recommended for the cases presented in this post. To address these limitations, alternative approaches are under investigation.

To learn more, see Boost GPU Memory Performance with No Code Changes Using NVIDIA CUDA MPS.