Robot manipulation systems struggle with changing objects, lighting, and contact dynamics when they move into dynamic real-world environments. On top of this, gaps between simulation and reality, and non-optimized grippers or tools often limit how reliably robots can generalize, execute long-horizon tasks, and achieve human-level dexterity across diverse tasks.

This edition of NVIDIA Robotics Research and Development Digest (R²D²) explores novel approaches to improving robot manipulation skills. In this blog, we’ll discuss three research efforts that use reasoning LLMs, sim-and-real co-training, and VLMs for designing tools for manipulation:

- ThinkAct: Vision-Language-Action Reasoning via Reinforced Visual Latent Planning

- Generalizable Domain Adaptation for Sim-and-Real Policy Co-Training

- RobotSmith: Generative Robotic Tool Design for Acquisition of Complex Manipulation Skills

We’ll also cover how robot manipulation can be improved using data augmentation and other recipes from the Cosmos Cookbook. This cookbook is an open-source resource that includes examples of real-world applications of NVIDIA Cosmos for robotics and autonomous driving.

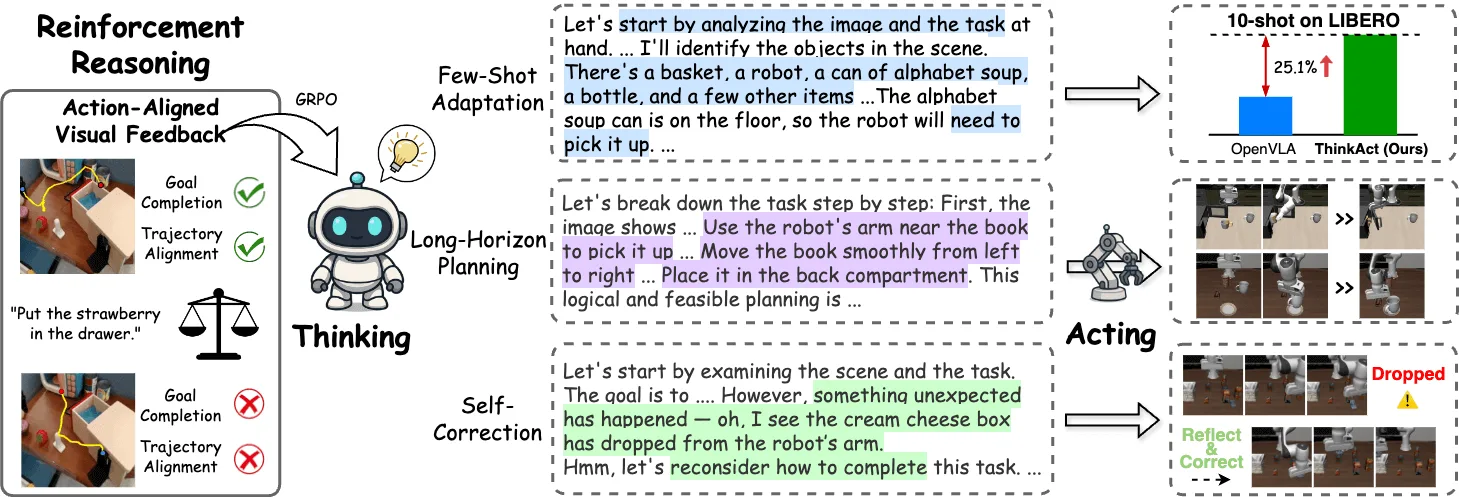

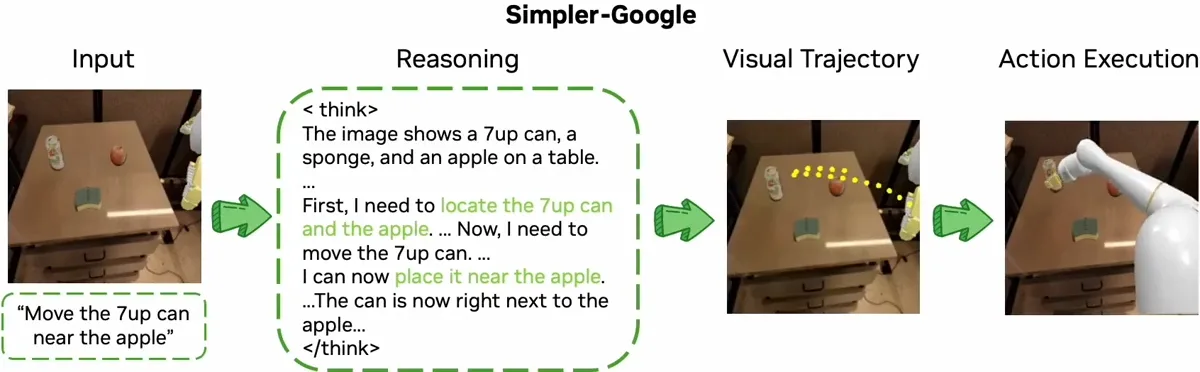

Improving robot reasoning and action execution with ThinkAct

In robotics, vision-language-action (VLA) models generate robot actions from multimodal instructions, like vision and natural language. A robust VLA should be able to understand and output complex, multi-step actions in dynamic environments. Current approaches to robot manipulation train end-to-end VLAs without an explicit reasoning step. This makes it difficult for VLAs to plan long-horizon tasks and to adapt to varying tasks and environments.

ThinkAct reduces this gap by integrating high-level reasoning with low-level action-execution in a dual-system framework. This “thinking before acting” framework is implemented via reinforced visual latent planning.

First, a multimodal large language model (MLLM) is trained to generate reasoning plans for a robot to follow. These plans are created using reinforcement learning, where visual rewards encourage the MLLM to make plans that lead to goal completion by following physically realistic trajectories. To do this, ThinkAct uses human and robot videos to perform reasoning based on visual observations. Training in this way ensures that the robot’s planning is not only theoretically correct but also physically possible according to visual feedback. This is the “Think” part.

Now onto the “Act” part. Intermediate steps in a reasoning plan are compressed into a compact latent trajectory. This representation contains essential intent and context from the plan. The latent trajectory then guides a separate action model, enabling the robot to execute actions in diverse environments. In this way, high-level reasoning informs and improves low-level robot actions in real-world scenarios.

ThinkAct has been tested on robot manipulation and embodied reasoning benchmarks. It successfully performs few-shot deployment, long-horizon manipulation, and self-correction in embodied AI tasks.

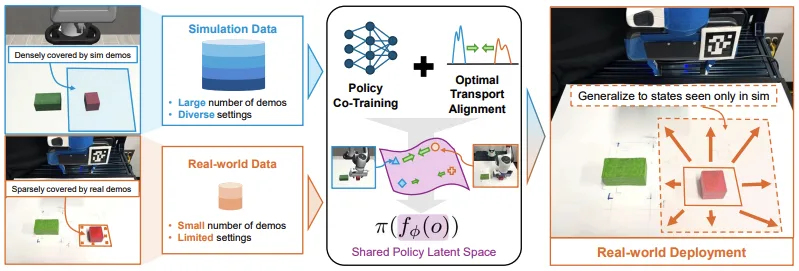

Co-training with the Sim-and-Real Policy

Training robots to perform manipulation tasks requires collecting data across diverse tasks, environments, and object configurations. A standard way of doing this is via behavior cloning, where expert demonstrations are captured in the real world. This sounds good in theory, but it’s expensive and doesn’t scale practically. Real-world data collection requires human operators to manually generate demonstrations or monitor robots, which is slow and limited by availability of robot hardware.

A solution is to collect demonstrations in simulation, which can be automated and parallelized to make data collection fast and easy. However, policies trained on simulation data don’t always transfer well to the real world. This is the sim-to-real gap that is observed because simulations cannot perfectly replicate complexities of real-world physics, dynamics, noise, and feedback.

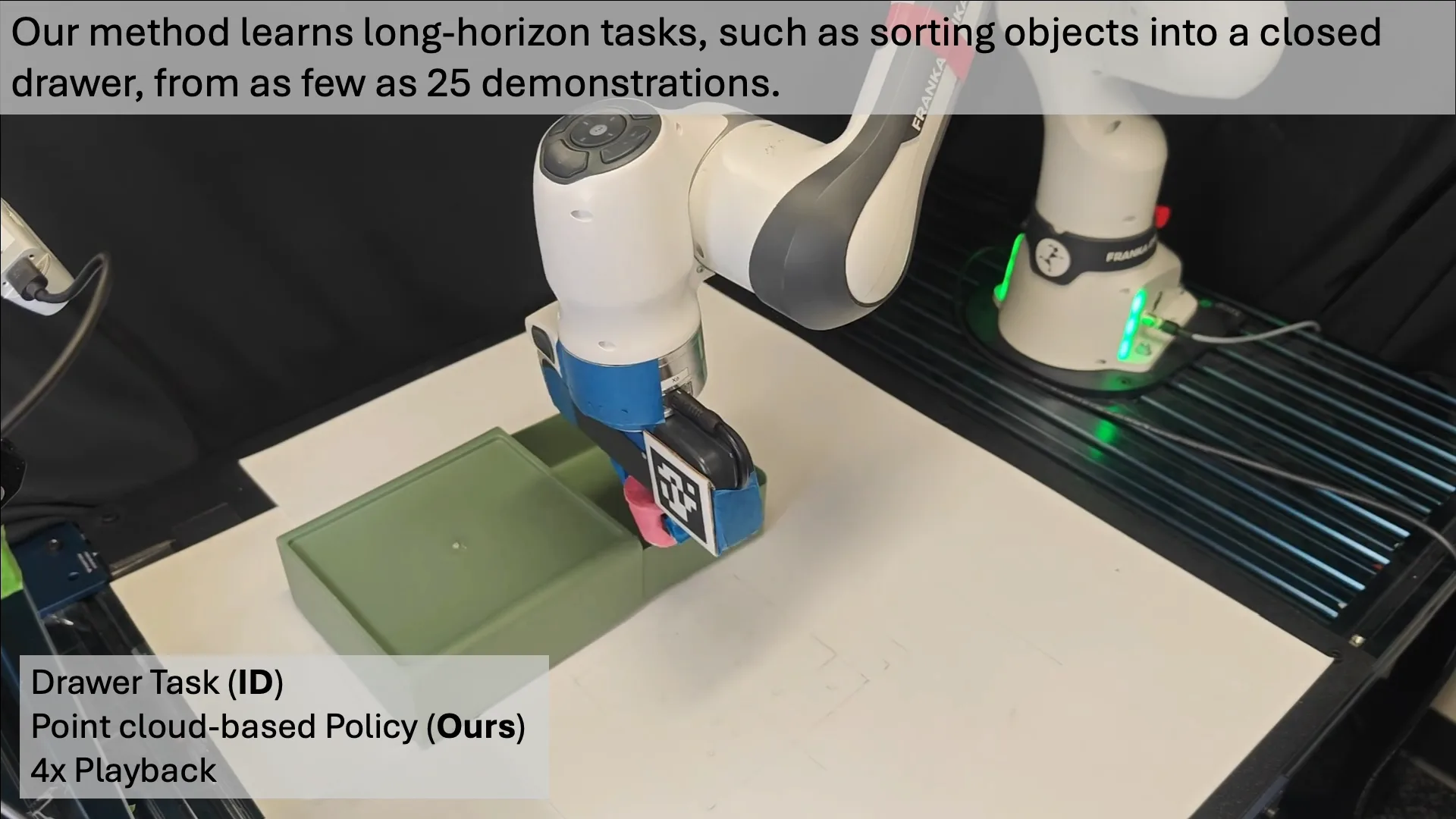

The sim-and-real policy co-training work bridges this gap by using both simulation and a few real-world demonstrations to learn generalizable manipulation policies. This is a unified sim-and-real co-training framework that learns a shared latent space where observations from simulation and the real world are aligned. It builds on the work presented in sim-and-real co-training and uses a better representation space for alignment. The representation also captures action-related information. The main idea is to align observations and their corresponding actions, so that the policy learns behaviors that work in both simulated and real settings.

These representations are learned via a technique called optimal transport (OT). OT helps policies detect similar patterns in simulation and real-world data so that the information needed for choosing actions stays the same, regardless of whether the input is simulated or real. There’s usually a lot more simulated data than real data, so this data imbalance is handled by expanding to an unbalanced OT (UOT) framework. UOT uses a sampling method that makes training more effective even when the datasets are different sizes.

Policies trained using this framework successfully generalize real-world scenarios, even if those scenarios appeared in just the simulated part of the training data. Both sim-to-sim and sim-to-real transfer was evaluated across robot manipulation tasks like lifting, cube stacking, and placing a box in a bin.

Improving robotic tool design with RobotSmith

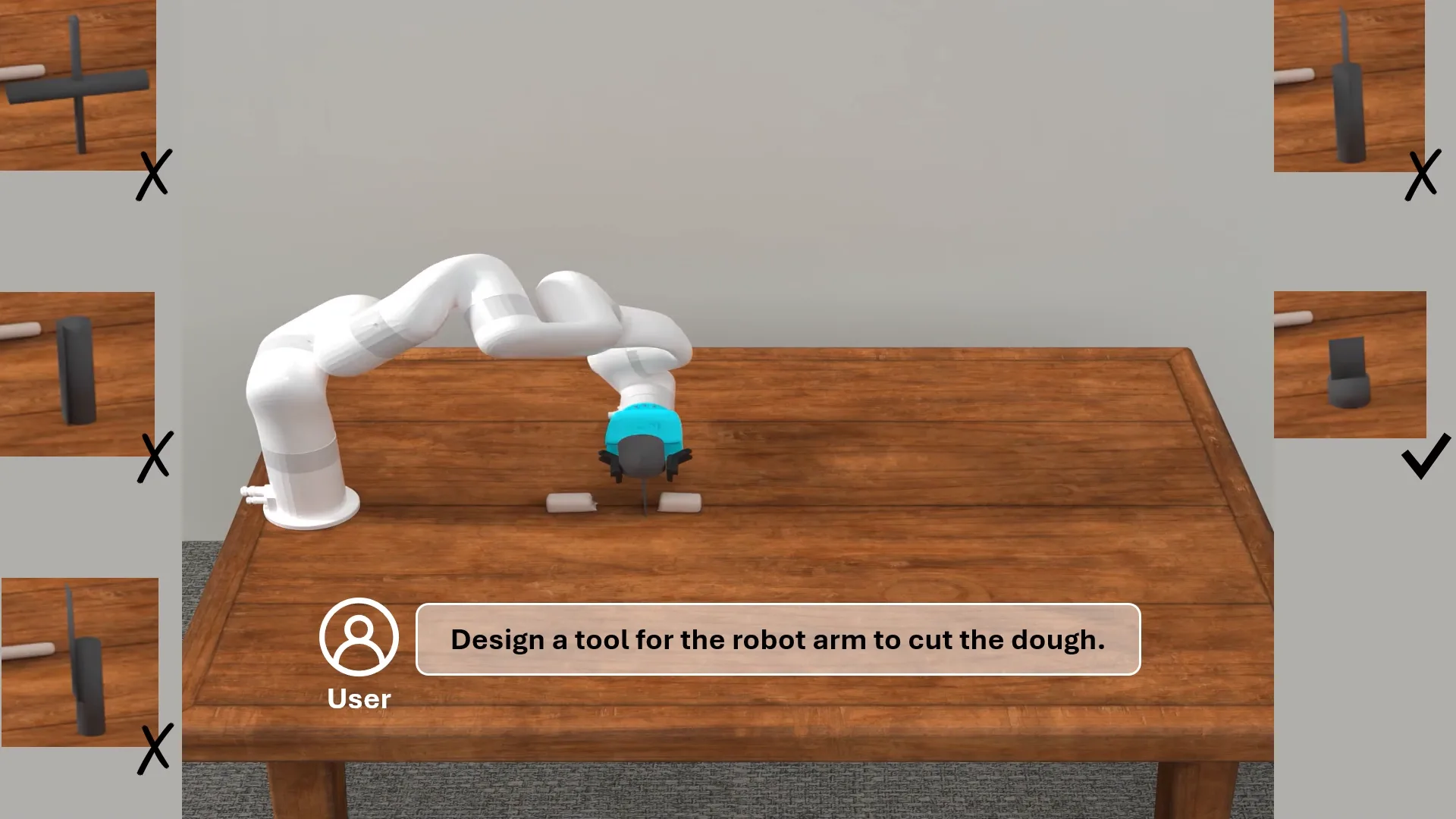

Most robot manipulation tasks involve the use of different tools and objects. Using tools is a necessary capability in robots to interact with their environments and perform complex actions. The problem is that tools designed for humans are difficult for robots to handle due to varying and complex form factors. Current approaches to robot tool design use predefined templates that aren’t customizable or 3D generation methods that aren’t optimized for this purpose.

RobotSmith solves this challenge by providing an automatic tool design framework using vision-language models (VLMs). VLMs are good at reasoning about 3D space and physical interactions, and understanding what actions can be performed by a robot with different objects. These key capabilities make VLMs very useful in effective tool design.

RobotSmith integrates this prior knowledge from VLMs with a joint optimization process in simulation to generate task-specific tools. The three core components are:

- Critic Tool Designer: Two VLM agents collaborate to generate candidate tool geometries.

- Tool Use Planner: Generates a manipulation trajectory based on the designed tool and scene. Candidate trajectories and grasps are executed and evaluated in simulation.

- Joint Optimizer: Tool geometry and trajectory parameters are jointly fine-tuned in simulation to maximize performance. This is important to eliminate suboptimal tool and trajectory pairs that may result in failed tasks.

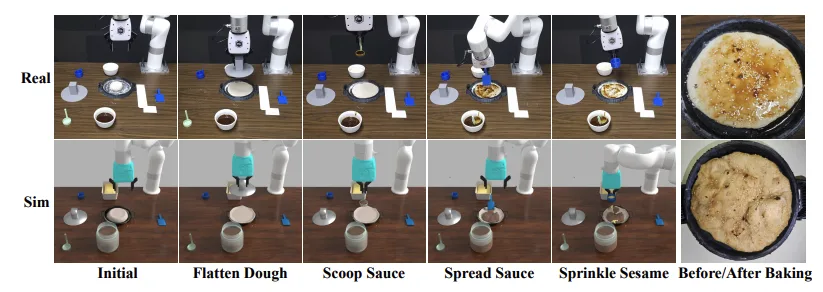

In this way, RobotSmith generates diverse tool designs for tasks like pushing, scooping or enclosing.

RobotSmith was evaluated in simulation and on real-world tasks. Find the complete list of experiments and results in the paper. One real-world test was making a pancake, for which the framework designed and used distinct tools for each step like flattening, scooping, and spreading dough. This demonstrated the framework’s ability to successfully perform long-horizon tasks.

Bridging the sim-to-real gap via the NVIDIA Cosmos Cookbook

We talked about the sim-to-real gap earlier in this blog, and discussed how synthetic data can be used for training robot policies. Realistic-looking and diverse synthetic datasets result in robust policies that transfer well to the real world. NVIDIA Cosmos open world foundation models (WFMs), specifically Cosmos Transfer, can be used to scale up synthetic datasets by generating photorealistic, diverse data from a single simulation. Find the entire workflow in the Robotics Domain Adaption Gallery in the cookbook.

In addition to this workflow, the NVIDIA Cosmos Cookbook offers step-by-step recipes and post-training scripts to quickly build, customize, and deploy Cosmos WFMs for robotics, autonomous, and agentic systems. It covers the following examples and concepts in-depth:

- Quick-start inference examples to get up and running.

- Advanced post-training workflows for domain-specific fine-tuning.

- Proven recipes for scalable, production-ready deployments.

- Core concepts covering fundamental topics, techniques, architectural patterns, and tool documentation.

The Cosmos Cookbook is a resource from the physical AI community for sharing practical knowledge about Cosmos WFMs. We welcome contributions including workflows, recipes, best practices, and domain-specific adaptations on GitHub.

Getting started

In this blog, we discussed new workflows for improving robot manipulation skills. We showed how ThinkAct uses a “thinking before acting” framework to reason and execute robot actions. Next, we talked about how using simulation and real data for training results in generalizable manipulation policies. We shared how RobotSmith generates robotic tool designs for optimized tool usage required during complex tasks. Finally, we saw how the Cosmos Cookbook provides examples and a shared place for physical AI projects using Cosmos models.

Check out the following resources to learn more about the work discussed in this blog:

- ThinkAct: Paper, Project website

- Generalizable Domain Adaptation for Sim-and-Real Policy Co-Training: Paper, Project website

- RobotSmith: Paper, Project website

- Cosmos Cookbook: Website, GitHub

ThinkAct, Generalizable Domain Adaptation, and RobotSmith, among many more papers from NVIDIA research teams, were accepted at NeurIPS 2025.

This post is part of our NVIDIA Robotics Research and Development Digest (R2D2) to give developers deeper insight into the latest breakthroughs from NVIDIA Research across physical AI and robotics applications.

Stay up-to-date by subscribing to the newsletter and following NVIDIA Robotics on YouTube, Discord, and developer forums. To start your robotics journey, enroll in free NVIDIA Robotics Fundamentals courses.

Acknowledgements

For their contributions to the research mentioned in this post, thanks to Ajay Mandlekar, Bohan Wang, Caelan Garrett, Chi-Pin Huang, Chuang Gan, Chunru Lin, Danfei Xu, Dieter Fox, Fu-En Yang, Haotian Yuan, Liqian Ma, Min-Hung Chen, Minghao Guo, Shuo Cheng, Tsun-Hsuan Wang, Xiaowen Qiu, Yashraj Narang, Yian Wang, Yu-Chiang Frank Wang, Yueh-Hua Wu, and Zhenyang Chen