This blog post is part of a series designed to help developers learn NVIDIA CUDA Tile programming for building high-performance GPU kernels, using matrix multiplication as a core example.

In this post, you’ll learn:

- How to implement high-performance matrix multiplication using NVIDIA cuTile: Understand the flow of Tile loading, computation, and storage.

- About the block-level parallel programming mindset: Shift from thread-level thinking to block-level thinking.

- Best practices for Tile programming: Learn performance optimization strategies from the code.

Before you begin, be sure your environment meets the following requirements (see the quickstart for more information):

Environment requirements:

- CUDA 13.1 or higher

- GPU architecture NVIDIA Blackwell (e.g., NVIDIA RTX 50 series)

- Python: 3.10 or higher

Install cuTile Python:

pip install cuda-tile

Note: cuTile is the next-generation GPU programming framework for NVIDIA. While it only supports optimization for the Blackwell (compute capabilities 10.x and 12.x) architecture, support for more architectures will be provided in upcoming releases of the CUDA Toolkit.

What is matrix multiplication?

Matrix multiplication is a fundamental operation in modern technical computing. It’s the operation that is the basis for solving systems of equations. It underpins graphics, simulations, optimization, and most of machine learning, and it maps well to high-performance hardware like GPUs.

Given input matrices A (MxK) and B (KxN), the formula for calculating an element in the result matrix C (MxN) is as follows.

From the formula, you can see that an element of C is computed by taking the dot product of a row of A and a column of B.

Tile programming can simplify the implementation while achieving excellent performance by dividing the output matrix into multiple tiles. Each Block is responsible for the calculation of one output tile, and cuTile automatically handles memory access and thread synchronization. Specifically:

- Each Block processes a (

tm×tn) tile of the output matrix C. - Loop over the K dimension, loading corresponding tiles of A and B one by one.

- Use

ct.mma()to perform matrix multiply-accumulate (automatically invoking Tensor Cores). - Finally, store the accumulated results back in global memory.

Figure 1 shows the calculation process, which is like an element-by-element algorithm, but in this case, the tiles take the place of individual elements

GPU kernel implementation

Having described the core idea, let’s look at the complete implementation code. The code is divided into two parts: the kernel running on the GPU and the launch code on the CPU, as shown in the code that follows.

import cuda.tile as ct

from math import ceil

import torch

# Type alias for compile-time constants

ConstInt = ct.Constant[int]

# Step 1: Define the kernel

@ct.kernel

def matmul_kernel(A, B, C, tm: ConstInt, tn: ConstInt, tk: ConstInt):

# 1.1 Get block ID and map to output tile position

# inside swizzle_2d, we access ct.bid(0) and output bidx and bidy

bidx, bidy = swizzle_2d(M, N, tm, tn, GROUP_SIZE_M)

# 1.2 Calculate the number of tiles along the K dimension

num_tiles_k = ct.num_tiles(A, axis=1, shape=(tm, tk))

# 1.3 Initialize accumulator

accumulator = ct.full((tm, tn), 0, dtype=ct.float32)

# 1.4 Loop over K dimension

for k in range(num_tiles_k):

# Load tiles from A and B

a = ct.load(A, index=(bidx, k), shape=(tm, tk))

b = ct.load(B, index=(k, bidy), shape=(tk, tn))

# Matrix multiply-accumulate

accumulator = ct.mma(a, b, accumulator)

# 1.5 Store result

ct.store(C, index=(bidx, bidy), tile=accumulator)

# Step 2: Launch the kernel

def cutile_matmul(A: torch.Tensor, B: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

# Choose tile sizes

tm, tn, tk = 128, 256, 64 # for float16

# Calculate grid dimensions

grid_x = ceil(m / tm)

grid_y = ceil(n / tn)

grid = (grid_x * grid_y, 1, 1)

# Create output and launch

C = torch.empty((m, n), device=A.device, dtype=A.dtype)

ct.launch(stream, grid, matmul_kernel, (A, B, C, tm, tn, tk))

return C

Now, let’s break down each key part step by step.

1. Define the GPU kernel

In cuTile, the @ct.kernel decorator is used to mark a standard Python function as a GPU kernel:

@ct.kernel

def matmul_kernel(A, B, C, tm: ConstInt, tn: ConstInt, tk: ConstInt):

# Kernel code here

This decorator indicates that:

- This function will execute on the GPU.

- Each block will run an independent instance of this function.

- It can’t be called directly and must be launched using

ct.launch().

2. Compile-time optimization: Constant type annotation

Notice that the parameters tm, tn, and tk use a special type annotation ct.Constant[int]:

ConstInt = ct.Constant[int] # Define type alias

def matmul_kernel(A, B, C,

tm: ConstInt, # Tile size along M dimension

tn: ConstInt, # Tile size along N dimension

tk: ConstInt): # Tile size along K dimension

This indicates they are compile-time constants. cuTile will generate specialized machine code for different tile size values, allowing the compiler to:

- Perform loop unrolling.

- Optimize memory access patterns.

- Generate optimal Tensor Core instructions.

3. Determining work scope: Block ID mapping

Each block computes a specific tile of the output matrix. Through the swizzle_2d() function, we obtain the index of the block currently being processed:

def swizzle_2d(M, N, tm, tn, GROUP_SIZE_M):

# Get the global IDs of the current CUDA block (CTA) in a 1D grid.

bid = ct.bid(0)

return swizzle_2d_from_bid(M, N, tm, tn, GROUP_SIZE_M, bid)

bidx, bidy = swizzle_2d(M, N, tm, tn, GROUP_SIZE_M)

The function of this code is to determine which tile of the output matrix the current block should process. To understand this process, let’s start with the grid division on the host side.

Step 1: Host-side grid division

When launching the kernel on the host side (explained in Section 3), calculate how many blocks are needed:

grid_x = ceil(m / tm) # Number of Blocks needed for M dimension

grid_y = ceil(n / tn) # Number of Blocks needed for N dimension

grid_size = grid_x * grid_y # Total Blocks

grid = (grid_size, 1, 1) # Defined as a 1D grid

mandn: Rows and columns of output matrix C.tm: Output tile size in row direction (M dimension) processed by each block.tn: Output tile size in column direction (N dimension) processed by each block.

Logically, launch grid_x * grid_y blocks and flatten them into a 1D grid: grid = (grid_size, 1, 1).

Step 2: Getting block ID in kernel

Inside the kernel, each block gets its unique identifier via ct.bid(0):

bid = ct.bid(0) # Return value range: [0, grid_size-1]

ct.bid(0)queries the current block’s ID in the x-axis dimension.- Parameter 0 represents the first dimension (x-axis), corresponding to the first element in the grid definition

(grid_size, 1, 1). - Each block gets a unique 1D coordinate: bid = 0, 1, 2, …, grid_size-1.

Step 3: Mapping 1D block ID to 2D tile coordinates

The problem now is that the block ID (bid) is 1D, but the output matrix is 2D. We need to know which row and column tile this Block should process. The swizzle_2d_from_bid() function determines which row and column tile the block is responsible for processing.

bidx, bidy = swizzle_2d_from_bid(M, N, tm, tn, GROUP_SIZE_M, bid)

Output result:

- bidx: The row index (M dimension) of the output tile the current block is responsible for. Range: [0, grid_x-1].

- bidy: The column index (N dimension) of the output tile the current block is responsible for. Range: [0, grid_y-1].

The specific mapping logic involves swizzling (used to improve memory access efficiency), which we will explain in detail in Section 4. For now, just understand that it converts a 1D Block ID into 2D tile coordinates.

5. Preparing the accumulator: Initializing output tile

Before looping through the K dimension, you need to create an accumulator to store intermediate results:

num_tiles_k = ct.num_tiles(A, axis=1, shape=(tm, tk))

accumulator = ct.full((tm, tn), 0, dtype=ct.float32)

num_tiles_k: Calculates how many tiles need to be processed in the K dimension.accumulator: A zero matrix of shapes (tm, tn) used to accumulate results.- Using float32 ensures numerical precision and avoids accumulation errors.

6. Core computation loop: Traversing the K dimension

This is the core of matrix multiplication. Now loop through every tile in the K dimension and accumulate the results:

for k in range(num_tiles_k):

# Load tiles

a = ct.load(A, index=(bidx, k), shape=(tm, tk), padding_mode=zero_pad)

b = ct.load(B, index=(k, bidy), shape=(tk, tn), padding_mode=zero_pad)

# Accumulate

accumulator = ct.mma(a, b, accumulator)

Loading data:

ct.load(A, index=(bidx, k), shape=(tm, tk)): Loads a tile from matrix A.index=(bidx, k): Specifies the coordinates of the tile to load in tile space.shape=(tm, tk): The size of the tile.padding_mode=zero_pad: Fills with zeros if the load data is out of bounds.

Matrix multiply-accumulate:

ct.mma(a, b, accumulator): Multipliesa*b, adds toaccumulator,and stores the result inaccumulator(mmastands for matrix multiply-accumulate)- When the shapes of

aandbmeet Tensor Core requirements, cuTile automatically invokes the GPU’s Tensor Cores to accelerate this operation.

After the loop ends, the accumulator stores the complete result for the output tile.

- Writing back results: Storing to global memory

Finally, write the calculated result back to global memory:

accumulator = ct.astype(accumulator, C.dtype)

ct.store(C, index=(bidx, bidy), tile=accumulator)

- First, convert the float32 accumulator to the output matrix data type.

- Use

ct.store()to write the tile back to the corresponding position in global memory.

Launching the kernel: Host-side code

Now launch the kernel from the host. First, look at the complete code.

def cutile_matmul(A: torch.Tensor, B: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

# Determine tile sizes based on dtype

if A.dtype.itemsize == 2: # float16/bfloat16

tm, tn, tk = 128, 256, 64

else: # float32

tm, tn, tk = 32, 32, 32

m, k = A.shape

_, n = B.shape

# Calculate grid dimensions

grid_x = ceil(m / tm)

grid_y = ceil(n / tn)

grid_size = grid_x * grid_y

grid = (grid_size, 1, 1)

# Create output tensor

C = torch.empty((m, n), device=A.device, dtype=A.dtype)

# Launch kernel

ct.launch(torch.cuda.current_stream(), grid, matmul_kernel,

(A, B, C, tm, tn, tk))

return C

Launching the kernel on the host side requires three key steps:

Step 1: Calculate grid size

Based on the input matrix dimensions and tile size, calculate how many blocks are needed:

m, k = A.shape # Matrix A dimensions: m rows, k columns

_, n = B.shape # Matrix B dimensions: k rows, n columns

# Calculate number of Blocks needed

grid_x = ceil(m / tm) # How many tiles needed for M dimension

grid_y = ceil(n / tn) # How many tiles needed for N dimension

grid_size = grid_x * grid_y # Total Blocks

grid = (grid_size, 1, 1) # Defined as 1D grid

ceil()rounds up to ensure all elements are covered (even if matrix dimensions aren’t divisible by tile size).- Flattening the 2D block layout into a 1D grid simplifies launch logic.

Step 2: Set tile size (compile-time constants)

Select appropriate tile dimensions based on data type:

if A.dtype.itemsize == 2: # float16/bfloat16 (2 bytes per element)

tm, tn, tk = 128, 256, 64

else: # float32 (4 bytes per element)

tm, tn, tk = 32, 32, 32

These parameters are passed to the kernel as compile-time constants:

tm: Output tile rows (M dimension).tn: Output tile columns (N dimension).tk: Size of tile loaded each time in K dimension.

Note: The tile size configuration here is an example. In practice, different GPU architectures require different parameter configurations to achieve optimal performance. Best configurations depend on M/N/K sizes, GPU architecture, shared memory size, register count, SM count, etc. In development, it is recommended to use performance analysis tools (like NVIDIA Nsight Compute) to find optimal parameters. TileGym provides an autotuner to automatically obtain optimal parameters.

Step 3: Call ct.launch() to start kernel

C = torch.empty((m, n), device=A.device, dtype=A.dtype) # Create output tensor

ct.launch(

torch.cuda.current_stream(), # CUDA stream

grid, # Grid dimensions: (grid_size, 1, 1)

matmul_kernel, # Kernel function

(A, B, C, tm, tn, tk) # Arguments passed to kernel

)

- Stream: Specifies which CUDA stream the kernel executes on (for asynchronous execution and multi-stream concurrency).

- Grid: Defines how many blocks to launch.

- Kernel function: The GPU kernel to execute (function decorated with @ct.kernel).

Argument tuple: All parameters passed to the kernel; tm, tn, and tk will be recognized by the compiler as constants.

Performance optimization: Swizzle

Earlier swizzling was introduced to improve performance. The code for swizzle_2d_from_bid is shown.

def swizzle_2d_from_bid(M, N, tm, tn, GROUP_SIZE_M, bid):

# Get the global IDs of a given CUDA block in a 1D grid.

num_bid_m = ct.cdiv(M, tm)

num_bid_n = ct.cdiv(N, tn)

num_bid_in_group = GROUP_SIZE_M * num_bid_n

group_id = bid // num_bid_in_group

first_bid_m = group_id * GROUP_SIZE_M

group_size_m = min(num_bid_m - first_bid_m, GROUP_SIZE_M)

bid_m = first_bid_m + (bid % group_size_m)

bid_n = (bid % num_bid_in_group) // group_size_m

return bid_m, bid_n

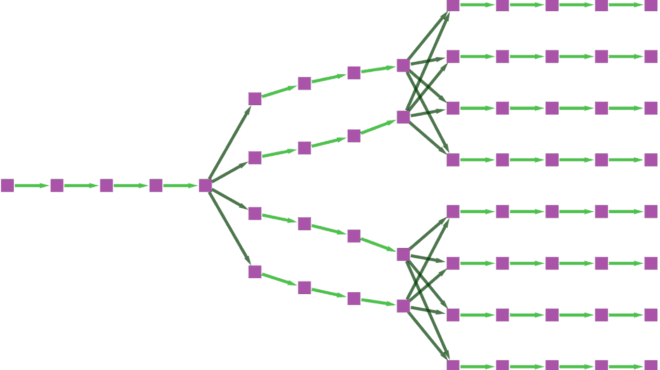

How does swizzle improve performance?

It re-maps block IDs to tile index through grouping and interleaving to use cache more efficiently.

Using four elements (shaded areas) of the output matrix as an example, the figure compares linear versus swizzled memory access

Method 1: Linear row access

- Calculates one row of data in the result matrix (e.g., four elements).

- Needs to read four blocks from the left matrix + all 16 blocks from the right matrix.

- Total memory access: 20 data blocks.

- Right matrix data is loaded frequently and replaced quickly, resulting in a low cache hit rate.

Method 2: Swizzling / tiled block access

- Reorganizes computation into 2×2 local blocks.

- Only needs to read eight relevant blocks from the left matrix + eight relevant blocks from the right matrix.

- Total memory access: 16 data blocks (20% reduction).

- Better data locality results in a higher cache hit rate.

Performance benchmarks

To verify the performance of the implemented matrix multiplication kernel, it was tested on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 (compute capability 12.0). You can find the complete benchmark code in the TileGym repository. Make sure to follow the installation instructions, and then you can run this and the other tests following the Quick Start instructions.

Test configuration:

- Data Type: float16

- Matrix shape: Standard square matrix (N×N)

- Test sizes: N = 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384 (i.e., 2^10 to 2^14)

The following figure shows the performance under different matrix sizes.

The results show that:

- At large matrix scales, the cuTile implementation can fully utilize the GPU’s computing power.

- Through appropriate tile size configuration and swizzle optimization, the cuTile implementation achieves over 90% of the performance compared to SOTA implementations (PyTorch calling cuBLAS).

Summary

This classic matrix multiplication example shows the complete process of implementing a GPU kernel using cuTile. Although matrix multiplication is simple, it contains the core ideas of Tile programming. Mastering these concepts will enable you to implement various high-performance GPU kernels using cuTile. Check out the full matrix multiply example and more in the TileGym repo, and start writing high-performance tile code today.