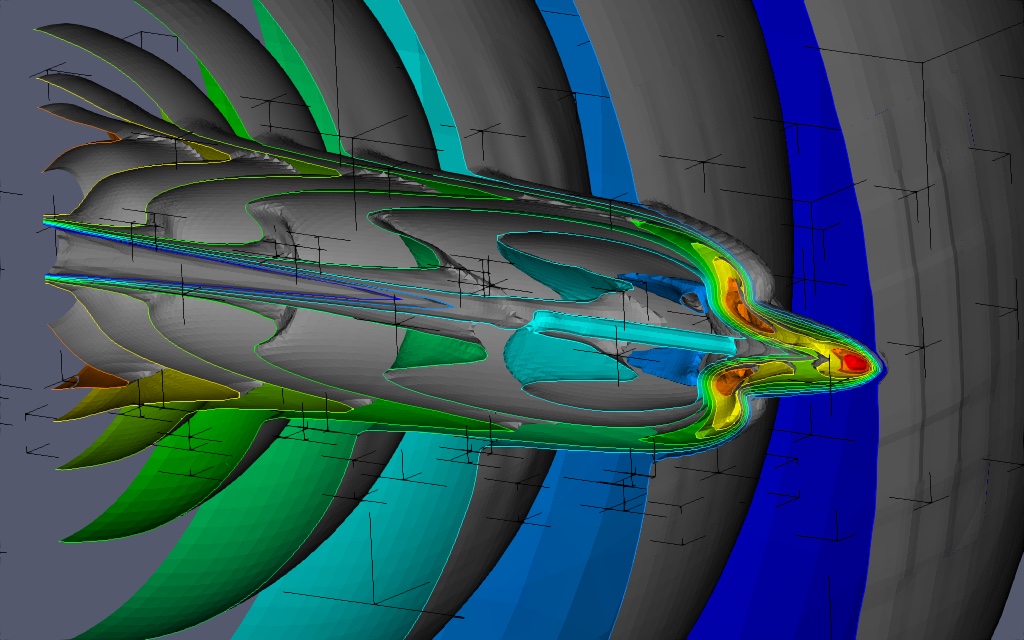

If you’re like me, you have a GPU-accelerated in-situ visualization toolkit that you need to run on the latest-generation supercomputer. Or maybe you have a fantastic OpenGL application that you want to deploy on a server farm for offline rendering.

Even though you have access to all that amazing GPU power, you’re often out of luck when it comes to GPU-accelerated rendering. The reason is that it’s not sufficient to enable OpenGL rendering on the GPUs, but it also requires running an X server on each node. For more information, see Interactive Supercomputing with In-Situ Visualization on Tesla GPUs.

Especially in an HPC setting, system administrators are often reluctant to have X server processes running on the compute nodes. Until recently, this was the only way to manage an OpenGL context. That’s where EGL comes in.

Over the past few years, a new standard for managing OpenGL contexts has emerged: EGL.

Initially driven by the requirements of the embedded space, the NVIDIA driver release 331 introduced EGL support, enabling context creation for OpenGL ES applications without the need for running an X server. However, it was still not possible to run legacy OpenGL applications under such contexts.

With the release of NVIDIA Driver 355, full (desktop) OpenGL is now available on every GPU-enabled system, with or without a running X server. The latest driver (358) enables multi-GPU rendering support.

In this post, I briefly describe the steps necessary to create an OpenGL context to enable OpenGL-accelerated applications on systems without an X server.

Creating an OpenGL context

The most common use case for OpenGL on EGL is to create an OpenGL context and use it for off-screen rendering. Another use case is a CUDA or OpenACC application that performs an operation that can benefit from the graphics-specific functionality of the GPU as part of the computation. For example:

- Solvers with domain boundaries expressed as triangulated surfaces

- Simulators that trace particle trajectories on a computational gird

- Codes that need to perform visibility tests for geometrical structures

The good news is that creating an OpenGL context with EGL is not rocket science! Just follow these five basic steps:

- Initialize EGL.

- Select an appropriate screen.

- Create a surface.

- Bind the correct API.

- Obtain a context from it.

The following code outlines the steps:

#include <EGL/egl.h>

static const EGLint configAttribs[] = {

EGL_SURFACE_TYPE, EGL_PBUFFER_BIT,

EGL_BLUE_SIZE, 8,

EGL_GREEN_SIZE, 8,

EGL_RED_SIZE, 8,

EGL_DEPTH_SIZE, 8,

EGL_RENDERABLE_TYPE, EGL_OPENGL_BIT,

EGL_NONE

};

static const int pbufferWidth = 9;

static const int pbufferHeight = 9;

static const EGLint pbufferAttribs[] = {

EGL_WIDTH, pbufferWidth,

EGL_HEIGHT, pbufferHeight,

EGL_NONE,

};

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

// 1. Initialize EGL

EGLDisplay eglDpy = eglGetDisplay(EGL_DEFAULT_DISPLAY);

EGLint major, minor;

eglInitialize(eglDpy, &major, &minor);

// 2. Select an appropriate configuration

EGLint numConfigs;

EGLConfig eglCfg;

eglChooseConfig(eglDpy, configAttribs, &eglCfg, 1, &numConfigs);

// 3. Create a surface

EGLSurface eglSurf = eglCreatePbufferSurface(eglDpy, eglCfg,

pbufferAttribs);

// 4. Bind the API

eglBindAPI(EGL_OPENGL_API);

// 5. Create a context and make it current

EGLContext eglCtx = eglCreateContext(eglDpy, eglCfg, EGL_NO_CONTEXT,

NULL);

eglMakeCurrent(eglDpy, eglSurf, eglSurf, eglCtx);

// from now on use your OpenGL context

// 6. Terminate EGL when finished

eglTerminate(eglDpy);

return 0;

}

Here’s a look at the individual steps of this minimal OpenGL context creation under EGL. The first step is to get a display object (eglGetDisplay()), which in this case is the default display. A display can, but doesn’t have to, represent a physical display attached to the system. So in the case of a headless node, this simply results in a display object for off-screen rendering.

Next, you must initialize EGL on this display (eglInitialize()). In addition to initializing EGL, this function returns the EGL version supported on the specified display. This can be handy if the application depends on a particular EGL version.

A display can support a range of configurations, so you have to specify the configuration used in this application. In this sample, I hard-coded a requested set of attributes for the configuration, like 8-bit color channels and the ability to generate an off-screen rendering pbuffer (I get to this in a second) or the size of the resulting surface. EGL then returns a set of configurations matching these requirements. In this case, you limit yourself to a single configuration.

Now you can start creating surfaces. What is a surface? Roughly speaking, a surface represents a window on your screen. Just that you don’t need to have a screen. So it’s a limited-size canvas to render into. In addition to the actual pixel data, a surface can contain auxiliary buffers, like a stencil or depth buffer. Here you just create an EGL surface for off-screen rendering, a so-called pbuffer (eglCreatePBufferSurface()).

You have almost all the pieces in place. The only thing that’s missing is that you must tell EGL what API you would like to use for rendering to this surface. In this case, select standard OpenGL (eglBindAPI()). An alternative would be to use OpenGL ES.

At this point, you can create the OpenGL context on this surface (eglCreateContext()) and make it current (eglMakeCurrent()) for future OpenGL operations.

EGL with multiple GPUs

The previous example assumes that you want to target the default display obtained through eglGetDisplay(). But what if you have multiple GPUs in your system and you want to use a specific one (possibly not managed by the X server) for your rendering tasks? Or what if you want to create an off-screen context and buffer not managed by the X server on a workstation with an attached display?

EGL provides an alternative, more powerful mechanism to obtain a display, eglGetPlatformDisplay(), which enables you to specify the exact display device to use, so you can select the GPU to work on in a multi-GPU configuration.

The following example code shows the process to obtain a display with eglGetPlatformDisplay().

#define EGL_EGLEXT_PROTOTYPES

#include <EGL/egl.h>

#include <EGL/eglext.h>

main()

{

static const int MAX_DEVICES = 4;

EGLDeviceEXT eglDevs[MAX_DEVICES];

EGLint numDevices;

PFNEGLQUERYDEVICESEXTPROC eglQueryDevicesEXT =

(PFNEGLQUERYDEVICESEXTPROC)

eglGetProcAddress("eglQueryDevicesEXT");

eglQueryDevicesEXT(MAX_DEVICES, eglDevs, &numDevices);

printf(“Detected %d devices\n”, numDevices);

PFNEGLGETPLATFORMDISPLAYEXTPROC eglGetPlatformDisplayEXT =

(PFNEGLGETPLATFORMDISPLAYEXTPROC)

eglGetProcAddress("eglGetPlatformDisplayEXT");

eglDpy = eglGetPlatformDisplayEXT(EGL_PLATFORM_DEVICE_EXT,

eglDevs[0], 0);

// ...

}

This example first queries the available EGL devices through eglQueryDevicesEXT(). Like all the EGL introspection routines, eglQueryDevicesEXT populates an array of devices and returns the number of devices found.

eglQueryDevicesEXT() is an EGL extension, which may not be supported by a specific EGL implementation. So you must include the EGL extension header, eglext.h, and enable extensions by setting the EGL_EXT_PROTOTYPES preprocessor macro. To get the desired extension function, you have to obtain the function pointers at runtime through eglGetProcAddress(), which takes the name of a function and returns a function pointer.

I’m omitting all error checking here for the sake of clarity, but production-quality code should gracefully handle the situation where eglGetProcAddress() returns a NULL pointer.

After obtaining a list of all available devices, select one that fits your purposes. Another extension, eglGetPlatformDisplayEXT(), enables you to use this device as the EGL display. All subsequent steps for creating the OpenGL context are then identical to the first example.

Managing your own OpenGL resources

In the first example, you used a pbuffer surface target for rendering, and let EGL manage all the buffers transparently, similar to the default frame buffer in a window. Instead of using an EGL surface, you can also manage all the OpenGL resources yourself.

In this case, you can skip eglCreatePbufferSurface() and after creating the OpenGL context, make it the current context:

eglMakeCurrent(eglDpy, EGL_NO_SURFACE, EGL_NO_SURFACE, eglCtx);

In this case, you specify EGL_NO_SURFACE instead of passing an appropriate surface. Managing OpenGL resources yourself—for example creating a frame buffer object (FBO) and attaching the appropriate textures and render buffers—can be particularly useful for CUDA/OpenGL interop because you can avoid an extra copy from the EGL surface to the CUDA-accessible OpenGL buffer.

Summary

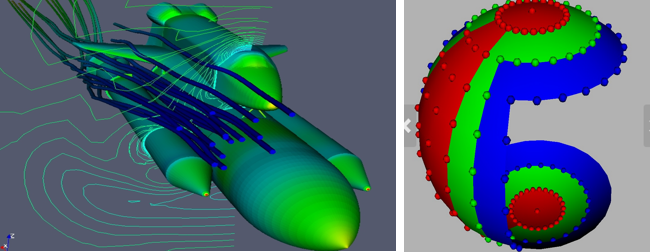

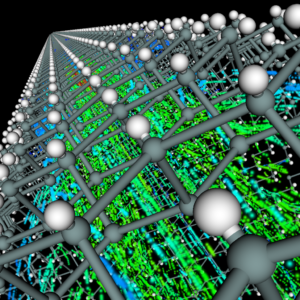

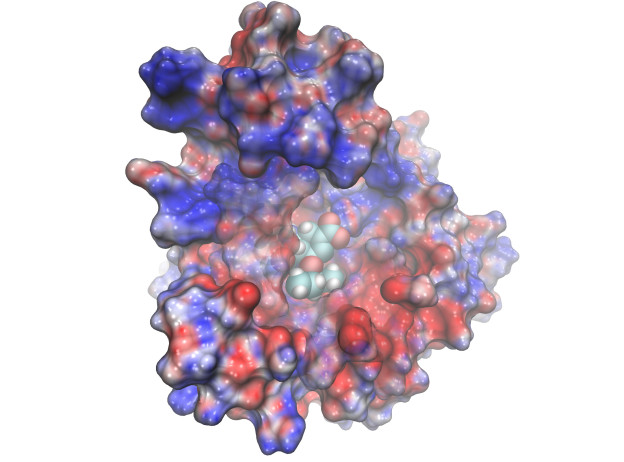

EGL provides valuable facilities for generating OpenGL contexts without the need for a running X server. This is particularly useful in HPC applications that need to render in a distributed fashion and eventually copy the rendered images off of the GPUs. Packages like Kitware’s Visualization Toolkit VTK or the molecular visualization toolkit VMD are already set up to use EGL for OpenGL context management and therefore no longer require a running X server for GPU-accelerated OpenGL.