Advanced Learning

This section will focus on the primary Nsight Graphics tools key concepts, advanced information and howto’s.

Important

This documentation is for individuals or companies under NDA with NVIDIA and may not be shared or referenced with any other party. For shareable documents, please see the documentation at this link

Introduction

Since the dawn of graphics acceleration, NVIDIA has led the way in creating the most performant and feature rich GPUs in the world. With each generation, GPUs get faster, and, because of that, more complex. In order to create applications that fully take advantage of the complex capabilities that exist in modern GPUs, you, the programmer, must have a deep understanding of how the GPU operates, as well as a way to see the GPU’s state as it relates to that operation. Lucky for you, NVIDIA Graphics Developer Tools has a simple mission; to provide an ecosystem of tools that gives you that super power.

This reference guide was created by experts on the Developer Tools team and is meant as a gentle introduction to some critical tools features that will help you debug, profile and ultimately, optimize your application.

Feel free to skip ahead to whichever section is most relevant to you. If you find any information lacking, please contact us at NsightGraphics@nvidia.com so we can make this reference better. In addition to this guide, we’re happy to work with individual developers on training. Lastly, if anything ever goes wrong, remember to use that Feedback Button at the top right of the tool window so that we have a chance to make the tool work better for you.

Thank you,

Aurelio Reis

SWE Director, Graphics Developer Tools

NVIDIA

Which version of Nsight Graphics should I use?

Pro vs Public

Nsight Graphics actually ships two different SKUs. There is the version available on the NVIDIA DevZone (here: https://developer.nvidia.com/nsight-graphics). This version includes all the latest features and is the best option for most users. In addition to the public version, we have a Pro (or what is sometimes referred to as the NDA) release. This is available either via “PID” or GRS (Game Ready Services). If you’re reading this, you likely already have access. If not, please contact NsightGraphics@nvidia.com and we’ll help you out.

The Pro version is meant for professional developers and includes a few additional features:

ucode-Mercury and SASS

ucode-Mercury and SASS are textual representations of the binary microcode that executes natively on NVIDIA GPUs. ucode-Mercury is available on Blackwell (RTX 50XX) and later GPUs, and SASS is available on Ada (RTX 40XX) and earlier GPUs. Being able to see the microcode generated from your HLSL, SPIR-V or DXIL intermediate code allows you to better understand what the GPU is actually executing.

NDA Metrics/Counters

NVIDIA shares the details of new technologies with Pro developers first, in addition to greater microarchitectural information. The following hardware units and related counters are only available in the Pro version:

RTCORE: the Turing Ray Tracing Accelerator

L1.5 Constant Cache

GPU MMU

Bandwidths, stall reasons, and a whole lot more

Early Access

The Pro version of Nsight Graphics will occasionally ship with features that are still being developed and in a stable preview state. This gives you the opportunity to get access to a valuable feature that could help you ship sooner, as well as to give you a chance to provide early feedback that may influence the development of that feature.

GPU Trace

What is it?

GPU Trace is a D3D12/DXR and Vulkan/VKRay graphics profiler used to identify performance limiters in graphics applications. It uses a technique called periodic sampling to gather metrics and detailed timing statistics associated with different GPU hardware units. With Multi-Pass Metrics, the tool can use multiple passes and statistical sampling to collect metrics. For standard metric collection, it takes advantage of specialized Turing hardware to capture this data in a single pass with minimal overhead.

GPU Trace saves this data to a report file and includes “diffing” functionality via a feature called “TraceCompare”. The data is presented as an intuitive visualization on a timeline which is configurable and easy to navigate. The data is organized in a hierarchical top-down fashion so you can observe whole-frame behavior before zooming into individual problem areas. Problems that previously required guessing & testing can now be visually identified at a glance.

In this section we will focus on the key-concepts the GPU Trace tool introduces and in depth explanation of the data it retrieves.

To learn how to use the tools go to the activities section in the user guide: here.

To understand the UI components GPU Trace UI section in the User Interface Reference here.

Overview of the GPU

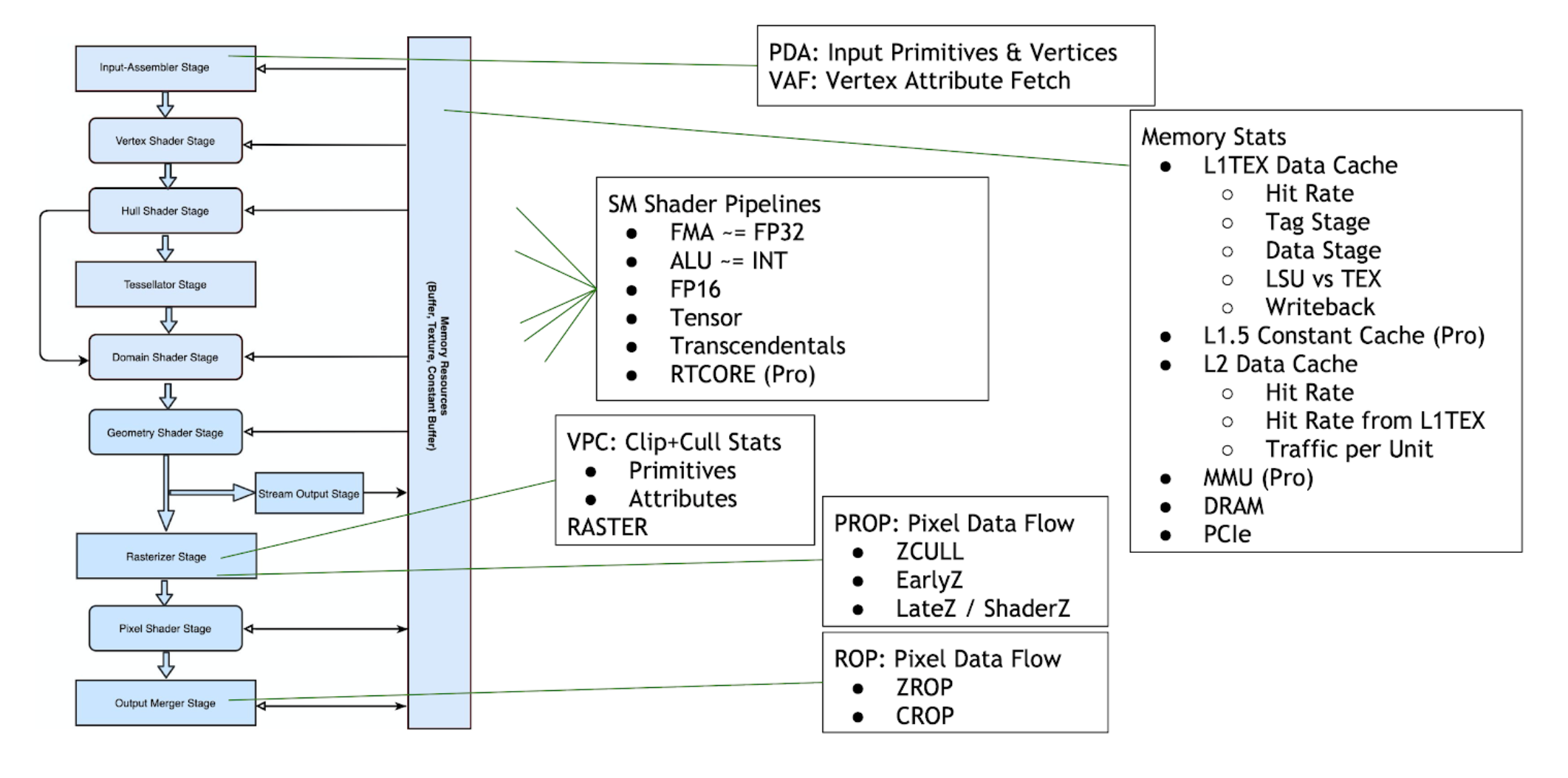

GPU Trace allows you to observe metrics across all stages of the D3D12 and Vulkan graphics pipeline. The following diagram names the NVIDIA hardware units related to each logical pipeline state:

Units Throughput

The Unit Throughputs row overlays the %-of-max-throughput of every hardware unit in the GPU. Multiple units can concurrently reach close to 100% at any moment in time.

Unit |

Pipeline Area |

Description |

|---|---|---|

SM |

Shader |

The Streaming Multiprocessor executes shader code. |

L1TEX |

Memory |

The L1TEX unit contains the L1 data cache for the SM, and two parallel pipelines: the LSU or load/store unit, and TEX for texture lookups and filtering. |

L2 |

Memory |

The L2 cache serves all units on the GPU, and is a central point of coherency. |

VRAM |

Memory |

|

PD |

World Pipe |

The Primitive Distributor fetches indices from the index buffer, and sends triangles to the vertex shader. |

VAF |

World Pipe |

The Vertex Attribute Fetch unit reads attribute values from memory and sends them to the vertex shader. VAF is part of the Primitive Engine. |

PES+VPC |

World Pipe |

The Primitive Engine orchestrates the flow of primitive and attribute data across all world pipe shader stages (Vertex, Tessellation, Geometry). PES contains the stream (transform feedback) unit. The VPC unit performs clip and cull. |

RASTER |

Screen Pipe |

The Raster units receives primitives from the world pipe, and outputs pixels (fragments) and samples (coverage masks) for the PROP, Pixel Shader, and ROP to process. |

PROP |

Screen Pipe |

The Pre-ROP unit orchestrates the flow of depth and color pixels (fragments) and samples, for final output. PROP enforces the API ordering of pixel shading, depth testing, and color blending. Early-Z and Late-Z modes are handled in PROP. |

ZROP |

Screen Pipe |

The Depth Raster Operation unit performs depth tests, stencil tests, and depth/stencil buffer updates. |

CROP |

Screen Pipe |

The Color Raster Operation unit performs the final color blend and render-target updates. CROP implements the “advanced blend equation” |

SM Occupancy Rows

The SM Occupancy row shows warp slot residency over time. Each Turing SM has 32 warp slots, where launched warps reside while they take turns issuing instructions.

For more information, please read this document’s shaderprofiler-keyconcept-scheduler section.

Additional information can be found in the following sections in the GPG Guide:

GPG: |

SM Micro-Architectural Organization. |

GPG: |

SM Shared Resources and Warp Occupancy. |

GPG: |

Modular Pipeline Controller (MPC). |

GPG: |

Life of a Compute Grid (Mapping the compute pipeline). |

GPG: |

Life of an Asynchronous Compute Grid. |

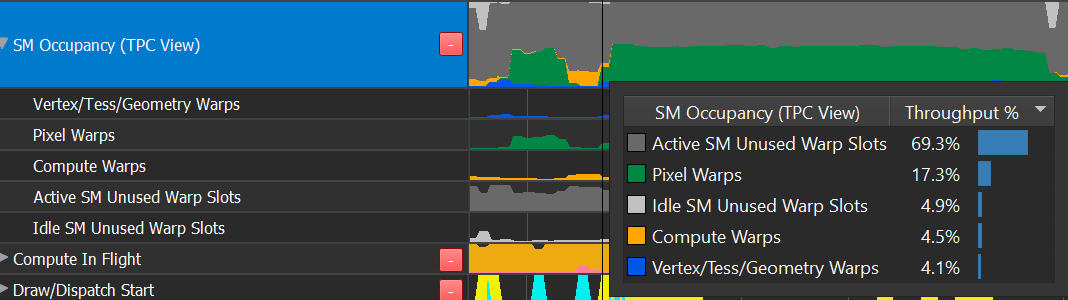

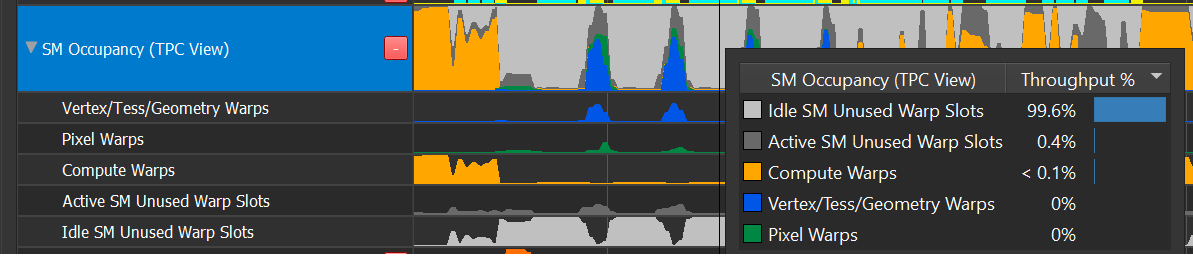

The row shows an ordered breakdown of warp slots. From top to bottom:

Idle SM unused warp slots (light gray)

The warp slot is a member of a completely idle SM

Indicates an easy opportunity to run additional shader work in parallel - additional shader warps can always be absorbed by idle SMs

Active SM unused warp slots (dark gray)

The warp slot is unused, but the SM is active – other warps are running on it.

Active SMs may be occupancy limited, implying these dark gray warp slots may be unable to absorb additional work

Compute Warps : compute warps across all simultaneously running Compute Dispatches, DXR DispatchRays, DXR BuildRaytracingAccelerationStructures, and DirectML calls

Pixel Warps : 3D pixel shader warps from all simultaneously running draw calls

Vertex/Tess/Geometry : 3D world pipe shaders from all simultaneously running draw calls

Mixed occupancy timeslice:

Low occupancy timeslice:

Asynchronous Compute

The only way to concurrently run compute and 3D is by simultaneously:

sending 3D work to the DIRECT queue

sending compute work to an ASYNC_COMPUTE queue

On Ampere, you can also dispatch concurrent compute workloads by dispatching it on both the DIRECT and ASYNC_COMPUTE queue.

You can detect whether a program is taking advantage of async compute in several ways:

The “Compute In Flight” row contains an “Async Compute In Flight” counter.

Observe when the compute warps executed on the SM Occupancy row, and determine if they were Sync or Async based on the color of the “Compute In Flight” row.

Look for multiple queue rows; the ASYNC_COMPUTE queue will appear as something other than Q0.

Compute will only run simultaneously with graphics if submitted on from an ASYNC_COMPUTE queue. This can disambiguate the SM Occupancy row.

See the GPU Programming Guide for more information:

GPG: |

Life of an Asynchronous Compute Grid. |

Warp Can’t Launch Reasons

When a draw call or compute dispatch enqueues more work than can fit onto the SMs all-at-once, the SMs will report that “additional warps can’t launch”. We can graph these signals over time to determine the limiting factor.

3D Shaders

3D warps may not launch due to the following reasons:

Register Allocation

Warp Allocation

Attribute Allocation (ISBEs for VTG, or TRAM for PS)

GPU Trace allows you to determine the following:

When Pixel Shaders can’t launch, for any reason.

When Pixel Shaders launch was register limited.

The warp-allocation limited regions in the Warp Occupancy chart. There are no free slots when there are no gray regions.

By deduction, if SM Occupancy shows a large region of pixel warps with no limiter visible, it either means

there was no warp launch stall, but rather very long running warps [unlikely], OR

warp launch was stalled due to attribute allocation.

Compute Shaders Compute warps may not launch due to the following reasons:

Register Allocation

Warp Allocation

CTA Allocation

Shared Memory Allocation

GPU Trace allow you to determine the following:

When Compute Shaders should be running in the Compute In Flight row.

When Compute Shader launch was register limited.

The warp-allocation limited regions in the Warp Occupancy chart. There are no free slots when there are no gray regions.

By deduction, if SM Occupancy shows a large region of compute warps with no limiter visible, it eithers means:

there was no warp launch stall, but rather very long running warps [unlikely], OR

one of the other reasons (CTAs, Shared Memory) was the reason.

Further disambiguating between 4a and 4b above:

Are the CTA dimensions (HLSL numthreads) the theoretical occupancy limiter for your shader? A thread group with 32 threads or fewer will be limited to half occupancy. Increasing to 64 threads per CTA will relieve this issue.

Is the shared memory size per CTA the theoretical occupancy limiter for your shader? (HLSL groupshared variables) Does (numCTAs * shmemSizePerCTA) exceed the per-SM limit of 64KiB [compute-only mode] or 32KiB [SCG mode]?

SM Throughput

SM Throughput reveals the most common computational pipeline limiters in shader code:

Issue Active : instruction-issue limited

ALU Pipe : INT other than multiply, bit manipulation, lower frequency FP32 like comparison and min/max.

FMA Pipe : FP32 add & multiply, integer multiply.

FP16+Tensor : FP16 instructions which execute a vec2 per instruction, and Tensor ops used by deep learning.

SFU Pipe : transcendentals (sqrt, rsqrt, sin, cos, log, exp, …)

Pipes not covered in the SM Throughput: IPA, LSU, TEX, CBU, ADU, RTCORE, UNIFORM.

LSU and TEX are never limiters in the SM; see L1 Throughput instead.

IPA traffic to TRAM is counted as part of LSU

RTCORE has its own Throughput metric

UNIFORM and CBU are unaccounted for, but rarely a limiter

Problem Solving:

If FP32 is high, consider using FP16 instead.

In theory, a 2X speedup is possible due solely to pipeline width.

In theory, a 3X speedup is possible by perfectly balancing FP32 and FP16.

L1 Throughput

GPU Trace exposes a simplified model of the L1TEX Data Cache, that still reveals the most common types of memory limiters in shader programs.

The Turing and GA10x L1TEX Caches share a similar design, capable of concurrent accesses:

Input: Simultaneously accepting an LSU instruction and TEX quad per cycle

Input: LSUIN accepts 16 threads’ addresses per cycle from AGU

Data: Simultaneously reading or writing the Data SRAM for LSU and TEX.

Writeback: Simultaneously returning data for LSU and TEX reads

Additional cache properties:

The T-Stage (cache tags), Data-Stage, and M-Stage are shared between LSU and TEX

The T-Stage address coalescer can output up to 4 tags per cycle, for divergent accesses. This ensures T-Stage is almost never a limiter, compared to Data-Stage

Per cycle, M-Stage can simultaneously read from L2 and write to L2. There is a crossbar (XBAR) between M-Stage and L2, not pictured above

In this simplified model, memory & texture requests follow these paths:

Local/Global Instruction → LSUIN → T-Stage → LSU Data → LSU Writeback → SM

Shared Memory Instruction → LSUIN → LSU Data → LSU Writeback → RF

Includes compute shared memory and 3D shader attributes

A few non-memory ops like HLSL Wave Broadcast are counted here

Texture/Surface Read → TEXIN → T-Stage → TEX Data → Filter → Writeback → SM

Includes texture fetches, texture loads, surface loads, and surface atomics

Surface Write → TEXIN… → T-Stage → LSU Data → Writeback → RF

Surface writes cross over to the LSU Data path

Memory Barriers → LSUIN & TEXIN → … flows through both sides of the pipe

Primitive Engine attribute writes to (ISBE, TRAM) → LSU Data

Primitive Engine attribute reads from ISBE → LSU Data

Local/Global/Texture/Surface→ T-Stage [miss!] → M-Stage → XBAR → L2 → XBAR → M-Stage → Cache Data SRAM

Turing Problem Solving

Turing reports the following activity:

Throughput of LSU Data and TEX Data

Separate counters in LSU Data for Local/Global vs. Shared memory

Throughput of LSU Writeback, and TEX Filter

By comparing the values of the available throughputs, we can draw the following conclusions:

All values are equal : most likely request limited

TEX Data > others : Bandwidth limited; cachelines/instruction > 1

TEX Filter > others : expensive filtering (Trilinear/Aniso) OR Texture writeback limited due to a wide sampler format (or surface format when sampler disabled)

LSU Data > others : Possibilities are:

Pure bandwidth limited

Cachelines per instruction > 1, causing serialization

Shared memory bank conflicts, causing serialization

Vectored shared memory accesses (64-bit, 128-bit) requiring multi-cycle access

Heavy use of SHFL (HLSL Wave Broadcast)

LSU Writeback > others : limited by coalesced wide loads (64-bit or 128-bit)

Note: this implies efficient use of LSU Data

LSU LG Data or TEX Data close to 100% : implies a high hit-rate

If Sector Hit Rate is low : may imply latency-bound by L2 or VRAM accesses

GA10x Problem Solving

GA10x reports the following activity:

Throughput of LSU Data and TEX Data

Separate counters in LSU Data per Local/Global, Surface, and Shared memories

Throughput of LSU Writeback, TEX Filter, and TEX Writeback

L1TEX Sector Hit-Rate - Reports the collective hit-rate for Local, Global, Texture, Surface - Note that shared memory and 3D attributes do not contribute to the hit-rate

By comparing the values of the available throughputs, we can draw the following conclusions:

All values are equal : most likely request limited

TEX Data > others : Bandwidth limited; cachelines/instruction > 1

TEX Filter > others : expensive filtering (Trilinear/Aniso)

TEX Writeback > others : limited wide sampler format (or surface format when sampler disabled)

LSU Data > others : Possibilities are

Pure bandwidth limited

Cachelines per instruction > 1, causing serialization

Shared memory bank conflicts, causing serialization

Vectored shared memory accesses (64-bit, 128-bit) requiring multi-cycle access

Heavy use of HLSL Wave Broadcast

LSU Writeback > others : limited by coalesced wide loads (64-bit or 128-bit)

Note: this implies efficient use of LSU Data

LSU LG Data or TEX Data close to 100% : implies a high hit-rate; cross-check against the L1TEX Sector Hit Rate

If Sector Hit Rate is low : may imply being latency-bound by L2 or VRAM accesses

See also in the GPU Programming Guide:

GPG: |

SM Memory Model |

GPG: |

Level 1 Data Cache (L1) |

GPG: |

Texture Unit (TEX) |

This covers the Pascal unified TEX pipe. The texturing-specific pipeline stages (TEXIN, TSL2, LOD, SAMP, X, MipB, W, D, F) are similar on Turing

L1.5 Constant Cache

The L1.5 Constant Cache is a read-only cache that holds data for:

Shader Instructions

Constant Buffers, Uniforms, and UBOs

Texture & Sampler Headers

The Turing architecture has a unified L1.5 cache that holds all of the above types of data. In previous architectures, Texture & Sampler Headers were held in a separate, smaller cache called TSL2. The L1.5 is also referred to as GPC Cache Controller or GCC.

There is one L1.5 cache per GPC, which serves all SMs in that GPC. Each request goes through the following cache levels, if it misses:

Shader Instructions: [SM] L0IC (I$) → ICC→ L1.5 → L2 → VRAM

Constants: [SM] IMC or IDC → L1.5 → L2 → VRAM

TS Headers: [L1TEX] TSL1→ L1.5 → L2 → VRAM

The L1.5 Constant Cache Hit Rates row shows total and per-type hit-rates

The L1.5 Miss Traffic row shows the total # of requests (originating from the SM) that missed in the L1.5. Missing in L1.5 implies high latency to L2, likely due to oversubscription to a certain type of memory access. Just look for blips here, as an indicator, since even low % values can be a serious indicator

Problem Solving:

If the L1.5 has significant miss-traffic, fix that first

Every L1.5 request implies a cache miss in an earlier cache (L0IC/ICC, IMC, IDC, TSL1) or a prefetch (ICC). If there is significant request traffic of a particular type, solve that

This implies, even if the L1.5 has a high hit-rate, that is not necessarily good!

Advice per memory type

Shader instructions

Reduce shader code size & complexity, especially in uber-shaders

Try “constant folding” by pre-compiling shaders with #defines per constant value, rather than passing dynamic constants. There are implied tradeoffs in memory usage and complexity of PSO management

Caveat: This can backfire if a large number of constant values result in many copies of the same shader

DXR: reduce the # of hit shaders

Try collapsing multiple shaders down to an uber-shader

Try to define fewer materials, including by parameterization or artistically

DXR: consider using shader libraries and shader linking, to avoid redundant library functions being compiled into each hit shader individually

Constants

Improve locality of accesses

Are indexed constant lookups heavily diverging?

Could a constant lookup be converted to a global (UAV)?

TS Headers and TSL1 Cache Thrashing

Is a single shader accessing a large # of textures? (large >> 16)

Are multiple draw calls’ shaders executing simultaneously, all accessing different textures or surfaces?

Could texture arrays be used instead of individual textures?

Could global memory be used instead of texture or surface

See also in the GPU Programming Guide:

GPG: |

Constant Caches |

GPG: |

Texture Inputs, for TSL1 |

GPG: |

Constant Buffer Versioning |

VRAM

The GPU’s VRAM is built with DRAM. DRAM is a half duplex interface, meaning the same wires are used for read and write, but not simultaneously. This is why the total VRAM bandwidth is the sum of read and write.

The VRAM Bandwidth row shows bandwidth as a stacked graph, making it easy to visualize the balance between read and write traffic. VRAM traffic implies either L2 cache misses, or L2 writeback. In either case, high VRAM traffic can be a symptom of poor L2 cache usage – either too large a working set, or sub-optimal access patterns.

PCI Bandwidth

The GPU connects to the rest of the computer via PCI Express (PCIe). PCIe is a full duplex interface, meaning separate wires are used for reads and writes, and these can occur simultaneously. This is why the PCIe row is displayed as an overlay, where reads and writes can independently reach 100%.

When the GR engine is idle (neither graphics nor compute running), it is often due to a data dependency, where a previous data transfer (DMA copy) must complete before draws or compute dispatches can start. Compare the GPU Active row against the Throughputs row to confirm that hypothesis.

Shader Profile

The Shader Profiler is a tool for analyzing the performance of SM-limited workloads. It helps you, as a developer, identify the reasons that your shader is stalling and thus lowering performance. With the data that the shader profiler provides, you can investigate, at both a high- and low-level, how to get more performance out of your shaders.

SM Warp Scheduler and PC Sampler

To understand PC Sampling data, you must first understand how the GPU executes shader instructions. Start by consulting the GPU Programming Guide:

GPG: |

SM Micro-Architectural Organization |

GPG: |

SM Shared Resources and Warp Occupancy |

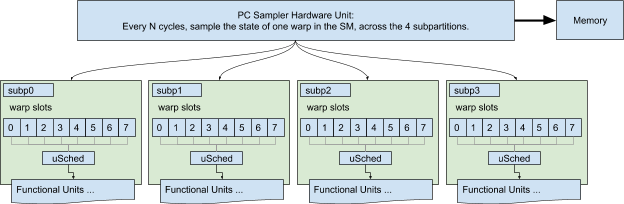

The following explains how the PC sampler works in conjunction with the hardware warp schedulers, to produce the final output.

Each SM has four schedulers, one per subpartition. On Turing, each scheduler governs 8 warp slots, with up to 8 launched & resident warps, and can issue an instruction from one <i>selected </i>warp per cycle. A warp can only issue an instruction if it is eligible : the instruction must be fetched, all of its operands available (with no data dependencies), and the destination pipeline must be available. When a warp is not eligible, it is said to be stalled; the <i>stall reason </i>describes why the warp is not eligible.

Each warp has a program counter register (PC) that points at the next instruction fetch location for the active threads in that warp. Inactive threads also have PC registers to support Independent Thread Scheduling, but inactive threads are irrelevant; the PC Sampler only inspects active threads’ PCs.

Nsight configures the PC Sampler hardware to sample a { PC, Stall Reason ID} at a regular interval across the entire SM (all four subpartitions); that data is streamed to memory. The tool then converts raw data into a count (Samples) per PC, and a count-per-reason per PC.

A compute-centric treatment of this topic can be found here.